On the Edge

The Competition for Resources Behind the War in Ukraine, and Why Donbas Is at the Heart of It.

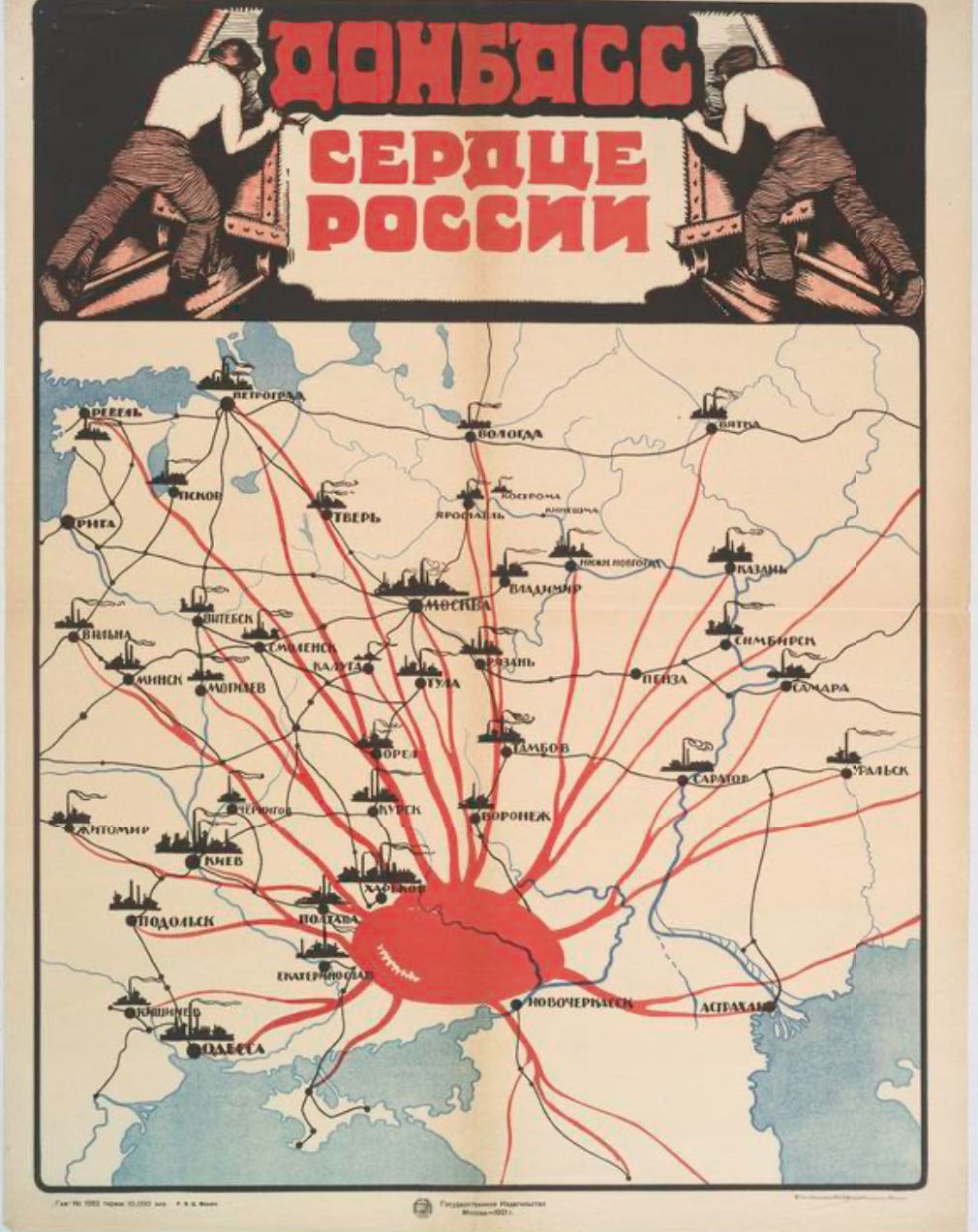

Picture Credit: New York Public Library

“The Edge ... There is no honest way to explain it because the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over. The others - the living - are those who pushed their control as far as they felt they could handle it, and then pulled back, or slowed down, or did whatever they had to when it came time to choose between Now and Later. But the edge is still Out there.”

― Hunter S. Thompson, Hell's Angels

This week, the ‘living’ are meeting to discuss the fate of Ukraine, as well as the soldiers and civilians on both side of a deadly and enduring conflict. Following the bilateral summit between the United States and Russia held in Alaska last Friday, Donald Trump told Ukrainian and European leaders that at the heart of any peace agreement with Vladimir Putin will be control of a place, the Donbas.

More than Words

Both Ukraine and Donbas have etymologies that reveal the nature of today’s conflict, and that set the scene for a struggle for ownership and control of some of the world’s most valuable natural resources.

To Ukrainians, ‘Ukrayina’ means our land, our country — the centre of a sovereign nation. To the Russian state, Ukraina has long meant something completely different: ‘on the edge’ - a ‘borderland’ of empire. The name Ukraine derives from the old Slavic root krai (край). It is a word with two intertwined meanings: ‘edge’ or ‘border’ — the limit of something; or ‘land’ or ‘region’ — a territory or place. In his 2021 essay on the ‘historical unity’ of Russians and Ukrainians, Vladimir Putin dismissed Ukraine’s sovereignty as an accident of history, insisting it was simply a borderland carved off from Russia. The Ukrainian and Russian state interpretations are fundamentally and fatally juxtaposed.

The etymology of the Donbas is more straightforward but is similarly revealing. The Donbas is shorthand for the Donets (Coal) Basin (‘Donestskyi Basein’ in Ukrainian) in eastern Ukraine. It is a resource and energy heartland, including a major industrial and mining hub, a shuttered shale gas frontier, and a crucial node in Europe’s power map. Its capture and control is central to Moscow’s war aims, not merely for land or people, but for the strategic leverage that energy has always given Russia.

Capital

Donbas represents a multi-trillion-dollar repository of industrial assets and critical minerals. It hosts Ukrainian coal, gas and mineral assets collectively worth an estimated $15 trillion.

Coal

Endowed with one of the largest coal deposits in the world, at around 20% of the total reserves of the former Soviet Union, Donbas was one of its industrial heartlands for much of the 20th century. At its peak, it produced nearly a third of Ukraine’s coal output and supplied steel mills in Donetsk, Horlivka, and Alchevsk and crucial power stations. The Donbas basin is estimated to contain more than 10 billion tonnes of proven coal reserves and remains key to Ukraine’s resource security.

This includes vast quantities of high-quality anthracite and coking coal, which are indispensable for metallurgy and steel production. Beyond coal, the Donbas is one of the world's major metallurgical and heavy-industrial complexes, home to the largest single producing area of iron and steel in Ukraine.

Gas

But a key strategic prize lies in what Donbas might have become: a new frontier for gas. As I explained in my book, The Edge, Ukraine has the second-largest gas reserves in Europe after Norway, most of which are untapped. It has the potential not only to become energy independent but also become a major exporter of gas. This would put it in direct competition with Russia’s Gazprom, previously the Soviet ministry of natural gas and now the largest gas company in the world.

In 2013, just a year before Russia annexed Crimea and shattered the project, Ukraine signed a $10 billion shale gas production-sharing agreement with Shell to develop the Yuzivska field, a vast shale resource straddling Donetsk and Kharkiv provinces. Its technically recoverable reserves are estimated at over 1 trillion cubic metres of natural gas (compared to Norway’s estimated 1.5 trillion cubic metres). There was an expectation that it might make Ukraine the largest non-Russian supplier in Eastern Europe.

The dash for gas created sparks for war. Conflict with Russia over the Donbas, local opposition and plummeting European gas prices in 2014 froze the Yuzivska project and preserved Gazprom’s dominance over Europe. Parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk provinces came under Russian-backed separatist control from 2014 and declared themselves ‘people’s republics’. On 21 February 2022, Putin announced that Russia was recognising them as independent states. On 22 February 2022, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced the mothballing of Nord Stream 2, a brand-new gas pipeline that had been completed in September 2021 - financed as to half by Gazprom and half by a consortium of European energy companies - that bypassed Ukraine. (Until then most Russian gas exports went to Europe through Ukraine through export pipelines controlled by Gazprom). On 24 February 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Donbas is not itself the central corridor for existing Russia-to-Europe gas pipelines (those run mainly through central Ukraine), but the region is an energy hub today in four critical ways. First, internal electrical grid leverage. Donbas power plants - Kurakhove, Sloviansk, Vuhlehirsk - once provided a significant share of Ukraine’s electricity. Their capture or destruction forces Ukraine to shift power across a grid already under constant missile attack. Second, the Crimea connection. Controlling Donbas, together with southern Ukraine, helps Russia secure the land bridge to Crimea. That means easier connections for power, water, and potentially pipelines — reducing Crimea’s reliance on vulnerable sea and air routes. Third, transit influence. While the big pipelines don’t run directly through Donbas, the region sits at the junction of east-west flows. Its capture complicates Kyiv’s management of internal gas distribution and strengthens Moscow’s bargaining power. Fourth: geostrategy. Holding the Donbas pushes NATO and Ukrainian forces further west, giving Russia strategic depth.

Resources

Donbas’s riches extend to a range of other vital resources. It contains enormous deposits of rock salt (with reserves in the billions of tons), which form the basis of a well-developed chemical industry. Significant mercury mining also takes place in the Donets Basin. Critically for the 21st century, the region is also rich in minerals essential for modern defence and green energy technologies, including lithium, tantalum, cesium, and strontium. The methane gas reserves associated with the coal deposits are estimated to exceed 2.5 trillion cubic metres.

The pursuit of the Donbas is not just about controlling the industrial assets of the 20th century, but also about securing the raw materials for the 21st. Russia's own economy is heavily dependent on the export of hydrocarbons. By seizing the Donbas's lithium and other critical minerals, Russia accomplishes several strategic goals: it acquires resources vital for its own future technological development, it removes a major potential competitor, Ukraine, from the global market for these materials, and it gains new leverage over European economies attempting to wean themselves off Russian fossil fuels. It is a strategic hedge against challenges to its hydrocarbon-based economy, aimed at ensuring Russia's continued economic performance and geostrategic influence.

The Resources that Bind the United States and Russia

The United States depends on Russia for key resources and has been notably circumspect in sparing Russia from direct application of its import tariffs.

While the United States does not depend on Donbas directly, there is a significant indirect overlap between its resource dependency on Russia and its interest in Ukraine in general, and Donbas in particular. Donbas shale gas in Yuzivska could have reduced Europe’s reliance on Russian gas, weakening Russia’s energy leverage. More broadly, Ukrainian titanium and alumina could have helped U.S. aerospace and industry diversify away from Russian metals. Perhaps most significantly, Ukrainian uranium – Ukraine is Europe’s largest nuclear fuel (uranium) producers and one the top 10 globally - could have eased the United States dependence on Russia.

The United States depends on Russia for its nuclear fuel. It imports a large share of enriched uranium from Russia and its allies (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan). Russia controls some 40% of the world’s uranium enrichment capacity. In 2021, before the war, about 20% of U.S. nuclear fuel imports came directly from Russia, and even more indirectly via Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. United States nuclear power plants (which supply some 20% of its electricity) are still dependent on this supply chain. Washington is now moving to build domestic enrichment capacity, but it will take years.

Russia is also a resource superpower in critical minerals used for aerospace, defence, and clean energy. In titanium, Russia’s VSMPO-Avisma is the world’s largest titanium producer. United States aerospace giants (Boeing, etc.) have historically sourced significant titanium from Russia for aircraft parts. In nickel, Russia (via Norilsk Nickel) is one of the top global producers. Nickel is critical for stainless steel and EV batteries. Russia supplies some 40% of global palladium, used in catalytic converters for cars, electronics, and even medical devices. The United States is heavily reliant on Russian palladium imports. In aluminium, Russia’s Rusal is a major global supplier. While the United States has domestic aluminium, Russian supply has remained important for industrial buyers.

We can expect the United States to be thoughtful in managing its resource security.

The Geostrategic Dimensions

Of course, there are strategic issues beyond energy. The Donbas is also a considered a centrepiece of a broader Russian project to revise the post-Cold War order, to permanently cripple the Ukrainian state, and to re-establish a dominant sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. Securing the Donbas would at once strengthen Russia economically and weaken Ukraine to the point of making it unsustainable.

By severing Ukraine from its industrial heartland, energy reserves, and a huge portion of its GDP, Russia would render Ukraine permanently weakened, de-industrialized, and dependent on Western financial support. This strategy is designed to make Ukraine a long-term economic liability for its allies, undermining its viability as a sovereign, pro-Western entity. Control of the Donbas is a strategic step towards causing Ukraine to fail as an independent state.

The Donbas is a critical piece of strategic terrain as part of a potential land bridge solution that would underpin Russia's southern flank from Crimea and offer power projection from the Black Sea.

Although Russia's annexation of Crimea in March 2014 was hailed as a major victory in Moscow, it created an acute strategic vulnerability. The peninsula, home to the headquarters of Russia's critical Black Sea Fleet, was transformed into a military exclave, a virtual island connected to the Russian mainland only by the yet-to-be-built Kerch Strait Bridge. It remained dependent on Ukraine for up to 85% of its fresh water via the North Crimean Canal and for all land-based logistical support. Russian-led forces instigated war in the Donbas just one month after the Crimean annexation in April 2014. It was the logical first step in securing a land bridge as the Donbas serves as the eastern anchor connecting it directly to Russian territory. The subsequent Russian offensives in 2022 to capture Mariupol and push westward through the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts were the execution of a strategic plan eight years later. The conflict in the Donbas was an expression of the strategic dilemma created by the annexation of Crimea, making the two theatres of war inextricably linked.

Russia's objectives in the Donbas are also linked to its broader strategy of re-establishing military dominance in the Black Sea region and projecting power beyond it. Control over the Donbas coastline on the Sea of Azov, a body of water that is now almost entirely a Russian lake, secures the northeastern flank of Crimea and provides additional ports and forward basing opportunities. For Moscow, the Black Sea is a strategic springboard for projecting power south into the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and North Africa. Russia's military intervention in Syria, which began in 2015, was logistically enabled and sustained by the Black Sea Fleet operating from Sevastopol. Gaining full control over Ukraine's entire southern coast, a project that begins with the Donbas, is therefore integral to this long-term geostrategic ambition. It would solidify Russia's control over the northern Black Sea, neutralise the Ukrainian navy as a factor, and enhance Russia's ability to challenge NATO's southern flank and influence events far beyond its immediate borders.

A Competition for Resources

The struggle for the Donbas is a multi-layered conflict. Its endowment of resources provides a global dimension to the challenge. And to any chances of resolving it.

In the meantime, as I write in The Edge, if we can avoid wasting 2/3rds of the world’s energy and other critical natural resources that the world is at war over, we may be better prepared for peace.

Jonathan Maxwell is the CEO of Sustainable Development Capital LLP and author of The Edge. He writes about energy, climate, finance, and geopolitics.